The Chicago Dancing Festival‘s annual engagement at the Museum for Contemporary Art has explored a variety of themes throughout its nine year history, most with a focus on maximizing the intimate and close-up setting provided by the wonderful Edlis Neeson theater. This year’s theme, “Modern Women” basically spanned the whole history of Modern Dance in a fascinatingly curated program featuring work by Isadora Duncan (1877-1927), Martha Graham (1894-1991), Crystal Pite, Pam Tanowitz, and Kate Weare.

There was genuine excitement surrounding this unique combination of choreographers. In email communications with Lori Belilove, Artistic Director of Isadora Duncan Dance Company, and Kate Weare, Belilove called the program “an upbeat expression of unbelievable joy,” and Weare stated that she was “excited to be included within this program because it acknowledges and celebrates the unique lineage of our art form as deriving from extraordinary women. At the same time, the program elegantly expresses the desire for a new generation of female choreographers to be recognized for their contributions.”

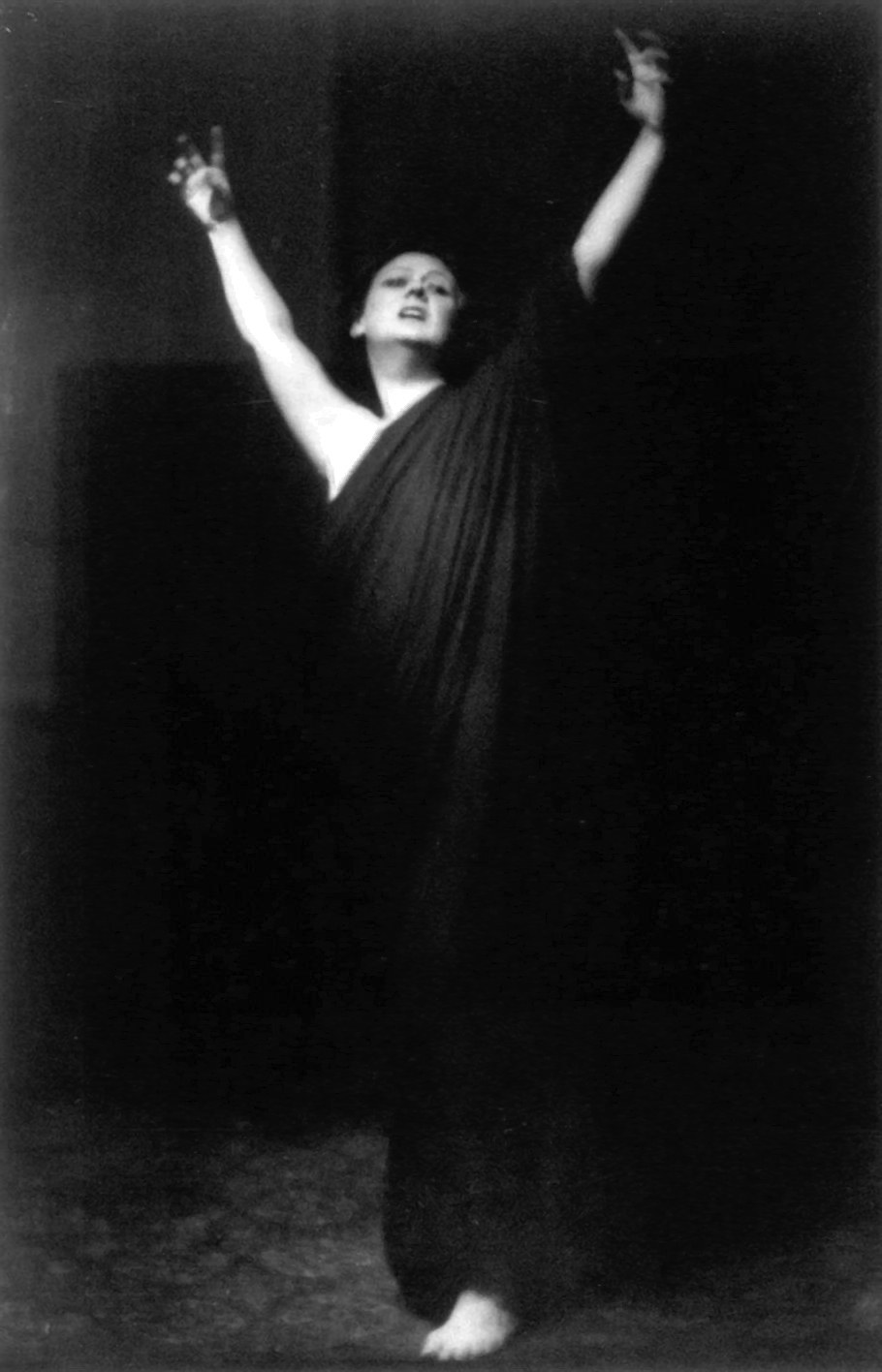

![Isadora Duncan by Arnold Genthe (1869-1942) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://i0.wp.com/www.artintercepts.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Isadora_Duncan_grayscale.jpg?resize=350%2C545&ssl=1)

In a phone conversation with Janet Eilder, Artistic Director of the Martha Graham Dance Company, she noted the lineage of modern dance as an artform that was driven by revolt, primarily by women. Modern dance, said Lori Belilove, is “a breaking from traditional, European sourced, balletic boundaries, and from my Isadoraian point of view, the medium where we can use dance to speak of our innermost stories and awarenesses.”

Pioneers of modern dance like Duncan and Graham, in addition to Loie Fuller, Katherine Dunham, Ruth St. Denis, Anna Sokolow, Pearl Primus, and so many more used dance as a conduit for social and political dialog during time periods in which women had few expressive outlets. “When Martha was beginning to make work,” said Eilder, “women had just gotten the right to vote.” Eilder suggested that women are less likely to be viewed as pioneers in dance today, citing Luke Jennings’ article in the The Guardian: “Where are all the female choreographers?” She suspects that the drought of women in leadership roles throughout dance could be attributed to the fact that women now have other ways to express radical ideas, and by highlighting the significance of women choreographers throughout the history of modern dance, the Chicago Dancing Festival hit the nail on the head.

“I think it is fantastic that Lar and the Chicago Dancing Festival are highlighting the strength and talent of the female choreographer,” wrote Tanowitz. “In this way, they are contributing to the paradigm shift that we all are experiencing and that can only lead to more and better opportunities for those who may not have had them before.”

“Women have been fighting for recognition recently and getting it— there is a long way to go,” wrote Lori Belilove. Tanowitz agreed: “I think it’s generally acknowledged that there is a deficit of opportunity and support for the female choreographic voice in the dance world. This could be a remnant of dominant male culture or there could be other reasons at play. This deficit is changing at the same time that many perceived stereotypes in our culture are being redefined. Early in my career I felt on the outside looking in and I welcome the forward motion that I do experience now, which allows me to explore my craft at a higher level.”

“There’s definitely a disparity in the dance world… when it comes to the visibility of female choreographers, said Glenn Edgerton, Artistic Director of Hubbard Street Dance Chicago, who presented Crystal Pite’s A Picture of You Falling (2008) on the Modern Women program. “The women who are with us, making good work, they aren’t always recognized or celebrated as much as they should be. In modern and contemporary dance, it’s been more equitable, at least to some degree. There’s Twyla Tharp, Martha Graham, Meredith Monk, Trisha Brown, going back you have Ruth St. Denis, Isadora Duncan, Katherine Dunham… The list goes on and on. At Hubbard Street, we’re not choosing choreographers by gender. We’re choosing choreographers because they’re good.”

Zachary Whittenburg, Manager of Communication at Hubbard Street, added, “We as all dance companies do have room to improve and increase our inclusion and support of women artists. We are not suggesting that Hubbard Street has declared ‘good enough.’ But we are trying and we’ve been a positive agent for change toward more equal representation in the field. We’re committed as an organization to promoting greater diversity in the field of dance, and will continue working toward that goal.”

Photo by Chris Alexander.

In considering the three living choreographers on the program, Kate Weare and Crystal Pite appear to rise directly from the dance lexicon laid down by Isadora Duncan, and later by Graham. The movement vocabularies of their release-based work is peppered with a sharpness and underlying narrative that give a nod to Graham. Edgerton wrote about Pite and her work in anticipation of the Modern Women program: “I find her work is always inventive, and it speaks to people in a very human way. She has the ability to draw a wide variety of emotions from an audience. [A Picture of You Falling] is somewhat unique in that it uses text and although it’s short, it really tells a story — although you only get that story at the end of the piece.” Pam Tanowitz was a bit of an anomaly on this program; her highly technical, unemotional Heaven on One’s Head (2014) clearly subscribes to a Cunningham aesthetic. However, Eilder reminded me that Merce Cunningham was a member of the Graham company for six years before rejecting her technique to create his own.

By nestling this program into the Chicago Dancing Festival, there was an opportunity to tell the history of Modern Dance to people who wouldn’t ordinarily have access to, or take an interest in it. That’s awesome, but in trying to encapsulate all of Modern Dance in an hour, the Dancing Festival severely watered down a rich and complicated story into an experience that might be comparable to riding It’s a Small World After All at Disneyland.

Don’t get me wrong, I love Disneyland.

But I’m also acutely aware that it’s a fabrication, even if an educational one. I’m not as confident that this distinction is apparent to Chicago Dancing Festival audiences. Rather, much of the general public is making the festival its one-stop shop for dance each year, perhaps thinking that THIS is representative of Dance (capital D). From my perspective, that is a dangerous assumption.

Don’t get me wrong, I love the Dancing Festival.

I love the ceremonious, stadium-style announcements between pieces, the full-cast curtain calls before each show, and the enormous effort that goes into producing a wildly popular, free (FREE!) dance experience that at times induces behavior not unlike the $99 sale at David’s Bridal. There’s nothing quite like it.

The question is, would Dancing Festival audiences be willing to go to a dance show in, say, November? Would they be willing to pay for it? Would they go see dance that is strange or challenging or obtuse? “Modern dance looks to the future, not the past,” said Kate Weare. “Moving forward is its heart and soul, which makes staying in touch with our past even more important. As an art form modern dance is a fascinating, full-blooded conversation through time and generation, housed in the body but springing straight from intellect and heart.” I can only hope that future Dancing Festivals continue to provide broad access to dance while challenging its audiences to participate in this conversation on a deeper level.