Joseph Lam, Director of the Confucius Institute at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor (CI), climbed a short set of stairs from the house of the Lydia Mendelssohn Theater up to the edge of the stage and immediately noted that he’d been given specific directions: Don’t touch the floor.

Indeed, it was a pristine white marley lining the Mendelssohn’s stage, whose unique white plaster cyclorama and exposed fly rails elicited a clean, sparse space for the North American premiere of Gu Jiani’s Right & Left on Sept. 26, 2015. It is perhaps not by accident that the sleek performance space was juxtaposed by opulent oak panels and plush red velvet seats in the house.

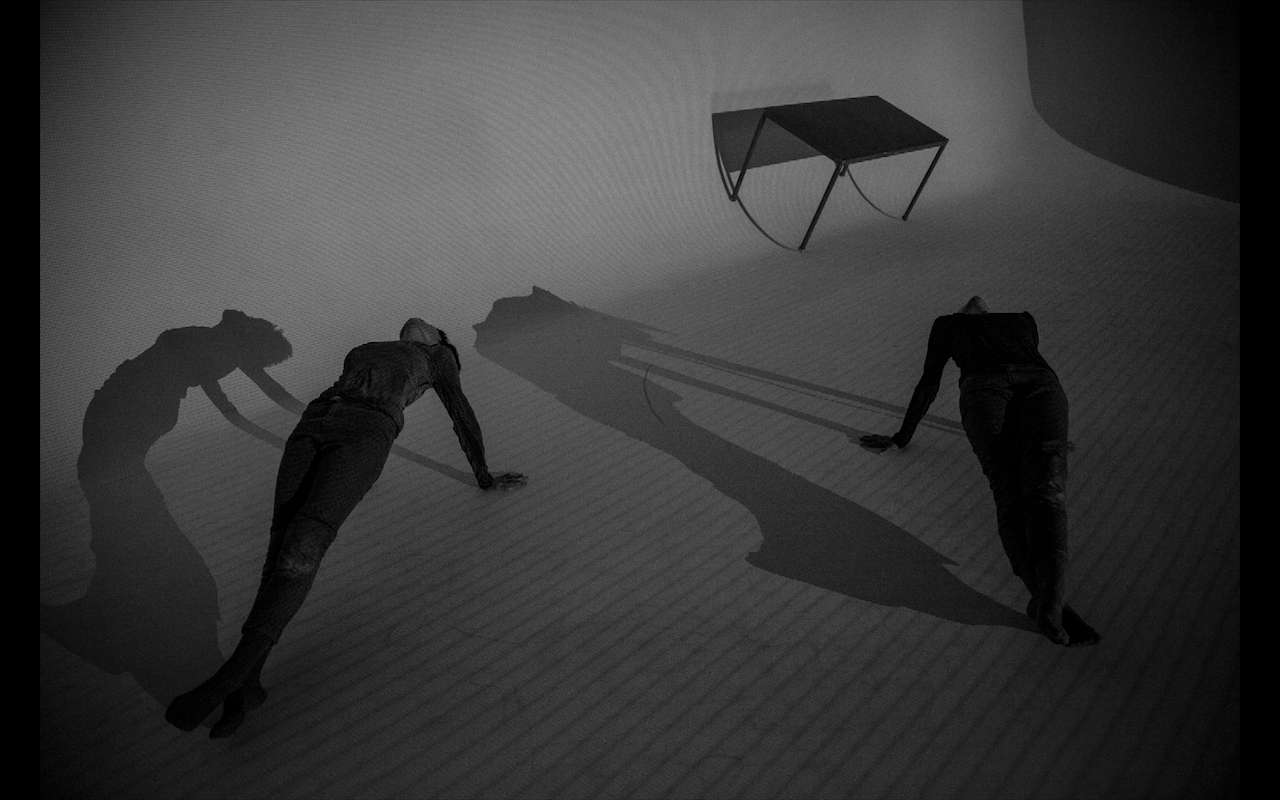

Right & Left seems to be about these sorts of juxtapositions, or rather, what we do with them. The two women onstage, choreographer Gu Jiani and her partner Li Nan, are both trained in Chinese and western concert dance, and their sylph-like figures are deceiving at first. The piece begins quite formally as the two women slide in and out of the ground, each with an épaulement characteristic of classically trained dancers. Gu’s movement is grounded in this vocabulary, until it isn’t.

What begins as a satisfying exercise on unison dancing degrades into an embodiment of the human experience through a series of long vignettes incorporating two simple stools and, near the end, a gray table sitting cockeyed upstage for the duration of the work.

It quickly becomes clear that this is no exercise – Gu is unafraid to break the rules of classical dancing as she and Li weave in and out of their light, or continue halfway into the wings as if the dancing extends beyonds its visual confines. The third player in Right & Left is Ah Ping, a projection artist manipulating light live throughout the performance. Although the collaboration began as a practical financial decision against hiring a conventional lighting designer, Ah Ping’s contributions turn out to be a critical piece of the puzzle. The stark white front light from the projector casts distorted shadows onto the back wall and floor while Ah Ping cuts and sections off parts of the stage, manipulating our perspective of the dancers.

In a more salient section, the seated Gu Jiani is tossed about like a rag doll as Li Nan asserts her power, the pair dimly illuminated by Ah Ping. Each toss back and forth seems to complicate the connection between the two women. Their movement evokes images of madonna and child in one moment, sadistic inamorata in the next. Right & Left doesn’t appear to be about love or relationships, exactly, but there is such a muddled, unemotional intimacy going on between its characters.

This is perhaps attributed to the delicate balance struck between discipline and reckless abandon; Gu demonstrates a masterful degree of restraint by not putting all her cards on the table. Rather, she sets a prop, a light, a movement idea, or another dancer in front of her and exploits every possibility it has before moving on. Whether this patience is attributed to ingenuity, rebellion, or simple economics – it’s enough to make the audience writhe in its seats, in a beautifully satisfying way.

In a larger sense, it’s difficult to discuss the work without also considering the context in which it’s been placed for this particular performance. Consider this: Gu Jiani is a Chinese contemporary choreographer performing for the first time in the US, represented by Ping Pong Productions, a Beijing-based producer lead by expat Alison Friedman. The Confucius Institute at the University of Michigan reached out to Emily Wilcox, a dance scholar and professor specializing in contemporary Chinese performance, and through her connection with Friedman, CI presented contemporary dance for the very first time (ergo Lam’s endearing reference to the white marley).

In his pre-performance announcement, Lam noted more than once the “very expensive, but very top quality” nature of the project, and rolled off a long list of philanthropic organizations who supported it. For this and so many other reasons, it’s frustrating that Right & Left was offered to the public for free. The fact that it occurred on a day in which hoards of Wolverines spent thousands upon thousands of dollars tailgating is downright infuriating.

Gu Jiani is making work in a place where there is no funding for independent artists, and the post-show discussion made note of the happy accidents in Right & Left that were financially motivated. And yet, the work has such a level of sophistication that every decision – whatever the reason – felt intentional and right. “Simplicity has a lot of options,” said Gu (translated by producer Alison Friedman) in the post-show Q & A.

Presenting work in the United States probably won’t change the way dance is funded in China, and we certainly have our own financial challenges to deal with in the arts. However, by bringing our attention to Gu Jiani and other artists making innovative work outside the US and Europe, the conversations surrounding the arts become richer, stereotypes begin to dismantle, and dance, on the whole, just gets better.

“China is transforming,” said Joseph Lam, “and Gu Jiani is reflective of that.”

—

Right & Left will premiere in Australia Oct. 15-17 at Festival Melbourne.