Following a highly successful pre-season weekend last month featuring up-and-coming choreographers, the official opening night of the Joffrey Ballet’s 60th anniversary season threw many of ballet’s conventions out the window. Entering the theater, we were greeted by an open main curtain and three dancers already onstage. We wanted to clap for the orchestra conductor (Chicago Philharmonic’s wonderful Scott Speck) as he entered, as we always do at the ballet, but the slow-motion montage of dancers and scenery including a moon, an archery target, and a tiny blue rock distracted us and made it feel weird. On the first swell of music, several women burst into one of the box seats (for which tickets were sold, btw), propped a foot on the ledge, and aimed bows and arrows at the target onstage.

This, I thought, was going to be a different kind of ballet.

The corps de ballet in John Neumeier’s Sylvia is nearly comatose, offering only slow-motion passes scattered throughout the ballet similar to that of the pre-show. Their purpose isn’t quite understood; maybe they are the gateway to some mythical land, or a metaphor for time standing still, or perhaps, as in other ballets, they are just trees, there to provide human scenery and fill up the stage. With the women in A-line green dresses and the whole corps striped across the eyes with blue make-up resembling Leonardo’s Ninja Turtle mask, there are few context clues as to why they are there, and the dancers likely feel the same way about performing these roles despite the enormous degree of control required to execute elaborate slow-mo partnering. Without them, however, Sylvia would leave much less of a “…huh?” taste in your mouth, why is perhaps why I love these Butoh-y forest nymphs of Neumeier’s ballet.

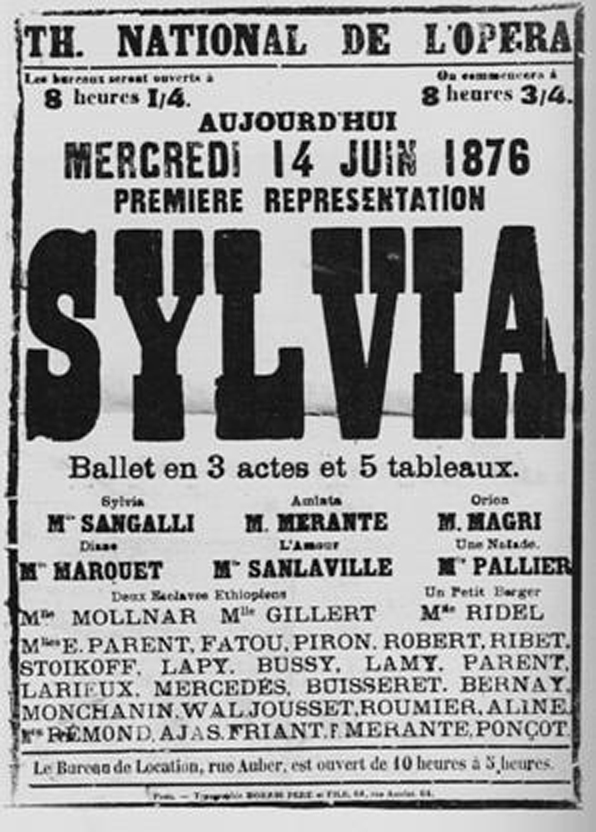

The women in Sylvia aren’t wilis, or sylphs, or snowflakes, but virgin huntresses, a clear departure from convention when the ballet was first created by Louis Merante in 1876. As Sylvia (brilliantly cast and danced by April Daly) and her gal pals romp through the forest, we learn that she has a complicated relationship with Diana, a sphynx-like leader of the pack danced by Victoria Jaiani. Sylvia and Diana are bonded by more than friendship but their mythical girl crush is broken by Eros (Temur Suluashivi). Suluashivi is a cheeky Eros, descending from above the stage like an angel in tiny asymmetrical white shorts. Sylvia is one of the few old ballets that actually keeps its female characters alive, sort of. It’s tempting to see Sylvia as a more “feminist” ballet – the strong, confident huntresses romp playfully through the forest in the first act, while the men, shepherds dressed up sort of like Mario and Luigi, bumble behind them with little scurries and silly pike jumps. The men are less central to the first act than the huntresses, and definitely not in charge.

Moreover, this is a very different Sylvia from the 19th century huntress Merante imagined, starting with her tiny shorts, leather vest, and Amelia Earhart cap. The eleven women burst on and offstage in a full-on run infused with staggered, boisterous Italian pas de chats, but the strength of Sylvia and Diana’s characters is diluted by the end of the first act as each is persuaded by a man. Falling prey to their respective lovers, however, provides fodder for a pair of stunning first act pas de deux and an exquisite second act.

Sylvia enters the second act dressed in red velvet against a stark white backdrop and a giant statue of a male figure. Feminist ballet or not, the scene symbolizes Sylvia’s sexual awakening as she dances with the company’s men, all dressed in tuxes. Some say that Clara’s Kingdom of the Sweets in the Nutcracker is a metaphor for her coming of age; Sylvia’s kingdom is more perhaps more overt than a giant puppet called Mother Ginger, but the idea is pretty much the same.

Throughout its history, critics have felt that Sylvia‘s one redeeming value is its magnificent score. While I can’t speak to previous iterations of Sylvia, and indeed, it’s hard not to love Leo Delibes’ splendid music, John Neumeier’s version of the ballet has so much more than that going for it.

Honestly, Sylvia‘s only problem is that nobody has ever heard of it. Oh, and it’s really long, so that might be a problem too.

I’ve spoken with a number of people who feel that Chicago is lagging behind other metropolitan dance hubs, not in the volume of dance but our ability to create and digest work that is innovative, new, or avant-garde. This perhaps was exemplified by the facial expressions of Joffrey’s season subscribers and the swell of confusion created by this Sylvia, a ballet first premiered by Paris Opera Ballet in 1997. Not everyone will get or like Sylvia; it’s challenging, and I’m pretty sure many will leave shaking their fists in the air, thinking, “What the hell was THAT?” In watching it, I’m reminded of reading about the uproar surrounding the use of concert music over scores created exclusively for ballet, the riots that broke from Nijinski’s iconic climax in L’Apres Midi d’un Faune, and the magical mystery tour of Robert Joffrey’s Astarte.

If we want ballet to evolve (we do), and if we want Chicago to compete in that evolution (we do), my hope is that companies like the Joffrey will persistently continue to challenge their audiences. The thing is – what people sometimes forget – is that by presenting what some might see as a weird head scratcher, the Joffrey Ballet is actually returning to what Robert Joffrey and his company used to be known for: innovation, edge (sort of), and modernity (circa 1997, but still…). These are not adjectives that Chicago’s dance goers tend to associate with the Joffrey Ballet, but in his own way, Artistic Director Ashley Wheater is carrying out Robert Joffrey’s vision, pushing his audiences, and in my opinion, winning.

—

The Joffrey Ballet presents Sylvia through October 25 at the Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University (50 E. Congress Pkwy). Single tickets are $32-155, available for purchase in the lobby of Joffrey Tower, 10 E. Randolph Street, as well as the Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University Box Office, all Ticketmaster Ticket Centers, by telephone at (800) 982-2787, or online at ticketmaster.com.