Movement Matters is a monthly column by Michael Workman that investigates performers whose work intersects politics, policy, and issues related to the body as the locus of socio-cultural dialogues on race, gender, ability and more.

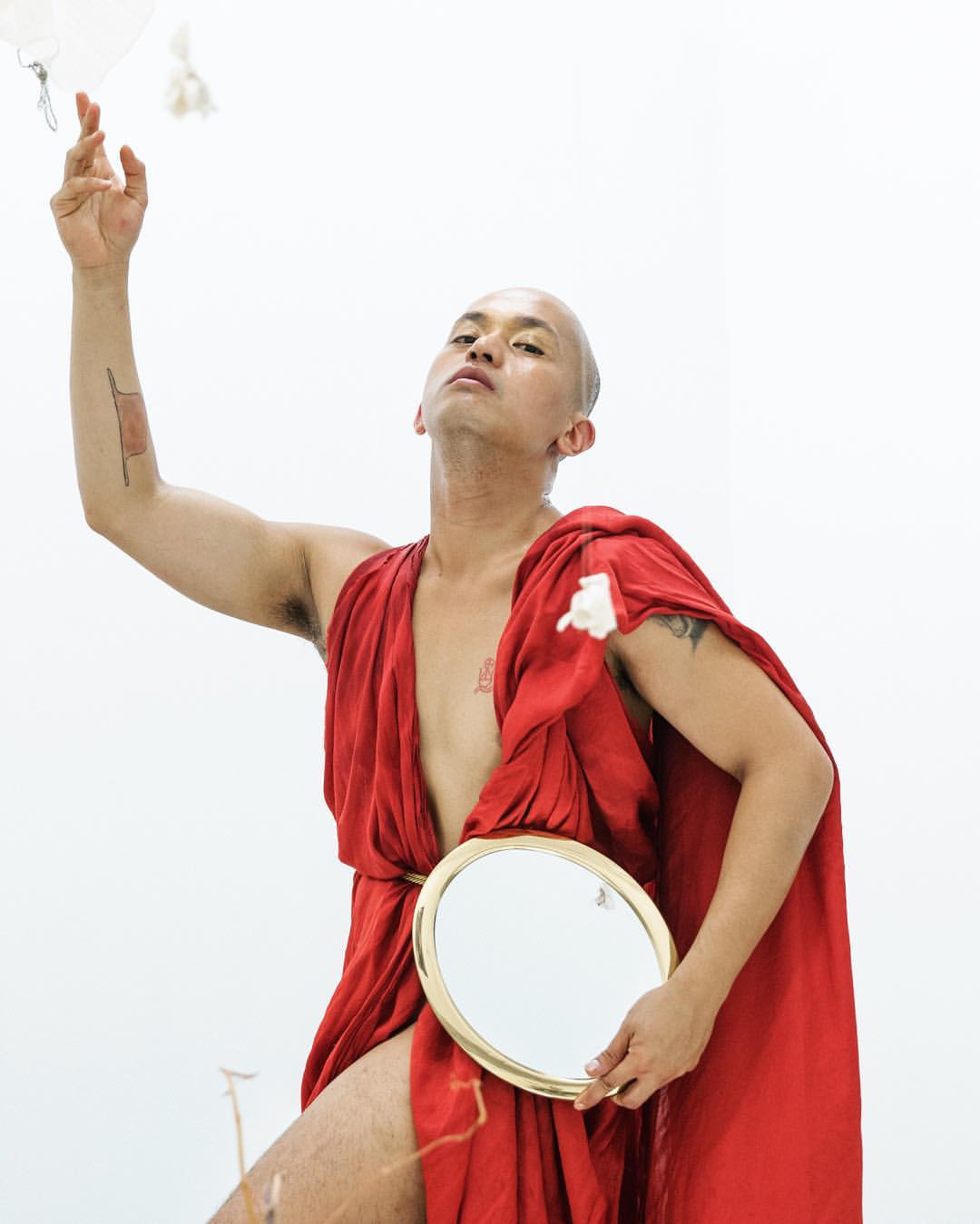

For this installment, we sit down with visual, performance and movement artist Kiam Marcelo Junio to discuss the influence of their military upbringing and career on their work, unexpurgating queer identity from toxic masculinity, and the artistic evolutions of their work across dimensions. An edited transcript of the interview is presented here.

Michael Workman: You spent most of your childhood outside the States, correct?

Kiam Marcelo Junio: I’m from the Philippines. I lived there, grew up there, and then moved to Japan when I was 10. I was adopted into my aunt’s family whose husband was in the Navy, and kind of grew up in this really international U.S. military community in Japan and then moved to California when I was 16. From there I did other things, and joined the Navy for 7 years.

MW: Do you have an artistic family?

KMJ: There are a lot of musicians in my family, but not necessarily visual artists. Pianists. Tuba. All kinds of everything really. A lot of pianists. But it was always a thing that you do on the side. I have one uncle who was a traveling musician, so he was kind of an influence a little bit, but my parents never encouraged me to do art; it was something I had to pursue on my own. When I joined the Navy at 19, I was prepared to turn that into a lifelong career. I thought I would go into the medical field afterward. I was working as a hospital corpsman, I think they called it. Even when I was in the military and doing all of that, every time I had free time, I was always making art whether I was doing photography or making collage or some other thing — mostly photography.

MW: Were you deployed then, too?

KMJ: I was deployed a few times on TD — temporary duty –but I was never in a war zone. I was down range but I pursued photography while I was in the military. It was a very accessible media, where I could really immerse myself in it and learn about the past while distinguishing between myself and the audience which I felt like worked for me as a bit of a shield. Photography, at that time, was becoming more and more—not pedestrian—but more colloquial in a way. More and more people were getting into photography as a kind of daily activity, before cell phones. When the iPhone came out was about the middle of my Navy career. So photography really gave me this platform to understand art-making and how to approach it in different ways but still have people around. So when I got out of the Navy—and I got out because I knew I was an artist and knew I had to pursue this field or I was not going to be happy—I left and the only school I applied to was [The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC)] because they gave me a scholarship. It was like: “Oh, I love Chicago.” I had done bootcamp just north of here, and my initial medical training was in Great Lakes. So when I was in medical training I’d come down to Chicago every other weekend or so and just come down by myself, go to events, and just be by myself and very independent, away from the military. So I took that feeling with me and I knew Chicago would be a good place to come back to and start over.

MW: So Chicago and SAIC was formative for you.

KMJ: In my first year at SAIC I was in photography, but I wasn’t doing a lot of photo work. I was doing mostly installation and video. And then outside of school I started taking burlesque classes at Vaudezilla and I was really intrigued by performance. I’ve always been a dancer and performer, really. An actor, vocalist—I was in a choir for years—a lot of other things but, again, performing really comes naturally to me and I knew that I wanted to see what it looked like in an art context away from theatre and away from the stage. SAIC has a really great performance community. I met a lot of people there who helped show me how to account for ideas in bodily movement, or create a space by inhabiting a space.

MW: It’s interesting how you were translating one art form into another.

KMJ: Yes, it was a progression from a flat image, from 3D reality into an image and then the flat image became another 3D space and then I realized the 3D space was one I was embodying and it was a translation of the “where is the art?” question, right? Is it the thing that you’re photographing, or is it you, the performer, who creates that image, or is it in the experience with the audience? I’m understanding how all of these different lenses operate and how they create the art in multiple layers. And I think early on I understood how my personal body is also a political body, is also a sensual body, is also a spiritual body. After leaving the military but before coming to Chicago, I took a yoga training course. It was a 1-month long residency that really delved into yoga philosophy and that really influenced how I was thinking about all of these layers I was perceiving. Then, applying that to art-making felt really naturally to me. I didn’t really realize until I was in school and saw the lack of representation of Filipino artists, and the Filipino-American experience—the intersection of that with being a veteran and thinking about those in terms of gender and coming into myself as a queer person.

MW: Yes, and especially with that background as a queer person in the military.

KMJ: Yes, and my response to it back then was a sense of camouflaging, playing the role of being quiet and doing my job, which is what my visual art is really rooted in was the experience of having to camouflage myself in hyper-masculine society. So, I think performance art, beginning in burlesque and then transforming into drag, was for me a way to take these identifiers that I wasn’t supposed to have or that I was supposed to work out of myself—like being feminine, speaking with an accent—I identify as femme and queer, trans in the larger umbrella sense of it, in the way I think people are familiar with it. I’m gender nonconforming.

MW: So, there’s this whole shift then in your earlier performance work I’ve seen, to bring performance into installation, making responses, for instance, to Felix Gonzalez-Torres.

KMJ: Yeah, I think definitely in the beginning.

MW: Taking that and articulating it into a whole other sense of what your voice is out there.

KMJ: My own agency in my work and in these spaces is always changing. In the last few years it’s been really interesting how people have taken note of what I’m doing and have really begun to understand where I’m coming from. That’s really encouraging and really beautiful and helped me to push even further and delve even deeper into where these ideas are coming from.

Please send questions, comments or tips to Michael Workman at michael.workman1@gmail.com. Each Spring and Fall, as a corollary to the Movement Matters column, we also present a series of symposia and performances at different locations throughout the city based on topics developed out of and indexed from both the columns and live discussions.

Each live event is filmed for adaptation to the Movement Matters web series, premiering in late 2017 on Open TV. Please join the Movement Matters Facebook page for information on additional forthcoming symposium, installments in our performance series, broadcast dates and times, archives of past columns, and to join in on future conversations.